Building College Heights

New campus’ lofty architecture embodied CSM’s equally lofty goals

Today’s College Heights campus opened in 1963 as one of the most sophisticated and ambitious community college campuses in the United States. It was an achievement long sought by College of San Mateo students and staff who for decades had shuttled between makeshift or partly built campuses.

Their need had gotten so dire that in 1954, accrediting officials shortened CSM’s customary five-year accreditation to three until college leaders committed to building a single, unified campus.

The rebuke shocked voters into action. Eleanore D. Nettle, a longtime civic volunteer and women’s president of San Mateo Junior College’s Class of ’31, won a seat on the Board of Trustees in 1956 with a pro-change platform that called for a new, growth-minded college president and a large new campus.

At a time when America had very few female elected officials, Nettle wielded the leadership to make change happen. She called for a countywide 25-year San Mateo Community College District Master Plan that led to today’s three-college system and helped fulfill California’s broader Master Plan for Higher Education.

Nettle also led the committee that hired CSM’s energetic next president, Julio Bortolazzo.

Soon after arriving in September 1956, Bortolazzo mounted what he called a “four-pronged attack” by faculty, students, trustees and Patron Association members to pass the bond measure that raised $5.9 million to buy the 150-acre College Heights site.

That measure, CSM’s first in 35 years, passed Oct. 15, 1957 in a landslide 13,706 to 4,641 vote. It purchased not only today’s College Heights but also the future Skyline College campus in San Bruno. A second bond campaign in March 1964 raised $12.8 million to finish the College Heights campus and begin Skyline and Cañada.

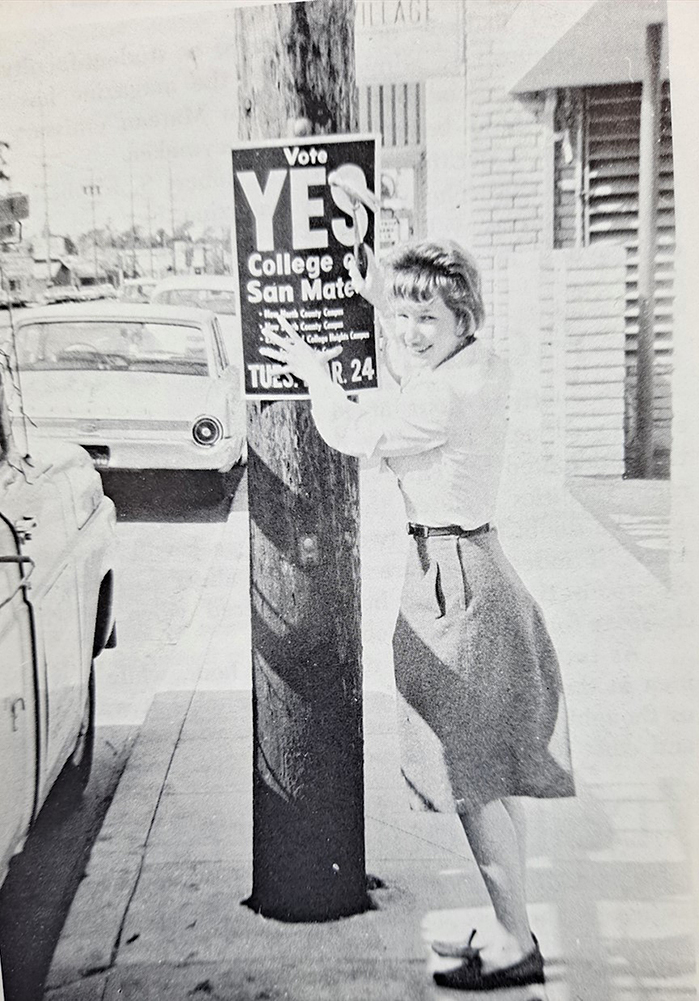

Students mobilized en masse to get out both votes. They met at Caltrain to pass out leaflets and vied for prizes for writing postcards and putting bumper stickers on cars.

On Sept. 30, 1963, College Heights opened with 5,500 students. The library, planetarium and fine arts center were still unfinished, classes started two weeks late, and incoming traffic backed up 19th Avenue to El Camino Real, but students were ecstatic. Wrote the San Matean: “We’ve waited almost as long as the Jews waited for Canaan.”

Fifty-one new instructors included language arts professor James Bell and visual artist Vince Rascon. They included swim coach Richard Donner and future Super Bowl coach Dick Vermeil, then 26, who was lured from Hillsdale High to coach the Bulldog backfield under new head football coach Cliff Giffin.

Prominent modernist architect John Carl Warnecke, whose commissions included the John F. Kennedy Memorial in Arlington, Va., designed the campus. Warnecke’s plan for CSM embodies in concrete the robust Cold War liberalism that Bortolazzo, and for that matter Kennedy, embodied in the flesh. Its formal axes, grand reflecting pools and repeating columnar bays with full-height glass refer to classical architecture and thereby classical learning. They express CSM’s intent that the prestige of higher education be available to all.

In addition to the second community college television station in America, the new campus had a theater, a museum, a planetarium and, in terms of square footage, one of the nation’s largest community college libraries. The library and the science buildings commanded the best views, because these sites were thought to be the leading edge of learning. They looked down on orderly rows of concrete hyperbolic paraboloids and folded-plate designs placed to add visual interest for observers above.

To ease campus access, U.S. Rep. Arthur Younger helped secure funding for State Highway 92—today named in his honor. Younger also twisted arms in Washington to finalize KCSM-TV’s license from the Federal Communications Commission. At its height, KCSM-TV’s “College of the Air” enrolled for credit 2,000 remote learners who came to campus only for exams.

Where Coyote Point and Delaware had a combined capacity of 2,600 students in 87 classrooms, College Heights had 146 classrooms with room for 4,800. Yet even this growth underestimated the Baby Boom population explosion. By 1965, day enrollment topped 8,100, making CSM the largest community college in Northern California. While CSM’s master plan projected 11,000 students countywide by 1970, actual enrollment in that year exceeded 20,000.

A third bond measure in March 1968 to mitigate these pressures was defeated. Voters were reacting partly to 1960s hippie-ish youth culture, which soured some people on public colleges, but mostly to soaring property taxes. In 1978, California voters passed Proposition 13 to cap property taxes, forcing immediate cuts and long-term statewide changes in budgets and funding. The era of seemingly limitless growth was over. Improvements seen today in CSM’s buildings, notably for energy efficiency and disabled-student access, thus took many years to achieve.

Nettle, meanwhile, continued to serve as trustee in a role that shifted to navigating the new austerity. She was re-elected seven times and retired in 1989.