Radio's Rooftop Roots

CSM’s nationally acclaimed broadcast program began as a 1920s nerd haven on Baldwin campus roof

“Who wouldn’t enjoy ... saying into the live mic of a local station, “And now, ladies

and gentlemen, the College Radio Guild presents ...”

– Richard Marsh, 1950s San Mateo Junior College broadcast instructor

Broadcasting at College of San Mateo is nearly 100 years old, eight years older than the Federal Communications Commission itself. It started as a campus radio club in 1926 and became a nationally acclaimed instructional program whose KCSM-FM and KCSM-TV produced dozens of technicians, engineers and on-air talent.

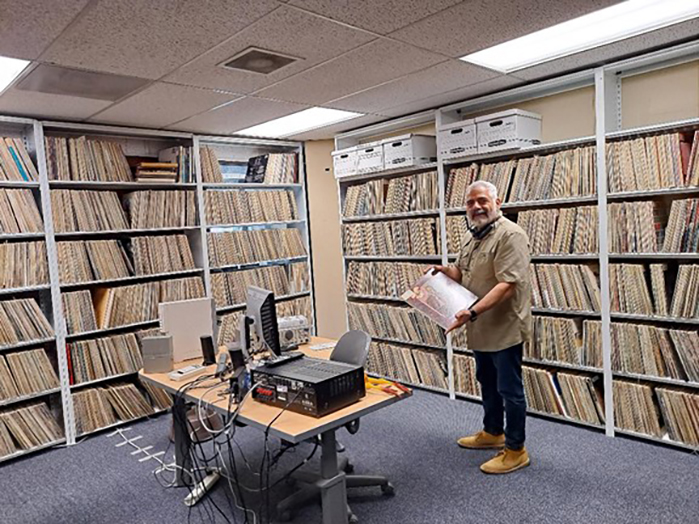

San Francisco Giants announcer Jon Miller, pathbreaking broadcasters Bonnie Chastain and Claire Mack, Armed Forces Radio chief Austin Peterson and radio DJ Art Leboe, who coined the phrase “Oldies But Goodies,” all learned their craft at College of San Mateo. Today, KCSM-FM 91.1 broadcasts an all-jazz format from the College Heights library and is one of very few noncommercial jazz stations in America.

CSM broadcast education, for decades more sophisticated than that of most four-year colleges, owed much of its quality and longevity to a single person, physicist and science Professor Jacob H. Wiens. From his arrival at then-San Mateo Junior College in 1938 to his retirement in 1973, Wiens, a Berkeley PhD, designed the antennas and much other equipment for the campus’ successive AM radio, FM radio and TV stations. He retired as director of KCSM-TV’s “College of the Air,” a remote-learning platform that at its height enrolled more than 2,000 students in credit courses delivered via the college’s UHF station on Channel 14.

But the KCSM story starts even farther back, with a tiny AM radio station in a closet on the Baldwin campus roof.

Broadcasting before dawn

6JU, as it was originally called, began in 1926. As W6YU, it became an official campus organization in September 1931 and was given a $10 yearly budget. Members competed to see who could reach radio stations farthest away. Because of how AM radio waves behave, transmission and reception were best in the very early morning. Radio Club members ascended the Baldwin roof before dawn. At first using Morse code telegraphy and, by 1940, voice transmission, they sent free messages anywhere in the world from anyone in the community. In 1931, they sent more than 300 such messages. Only sporadically, however, could the station broadcasting around 1400 on the AM dial be heard on home radios outside San Mateo.

In 1941, an FCC ruling that college radio stations must be FM augured big changes in SMJC’s program because the FM equipment was much more expensive. After America entered World War II, many West Coast stations were temporarily silenced. Authorities feared enemy aircraft would use the signals to locate civilian targets. W6YU, however, soldiered on as San Mateo County’s civilian defense station. Faculty and staff took to the roofs as civilian defense spotters to keep San Mateo, and the station, safe.

Wartime made electronics crucial

Wiens, meanwhile, temporarily left SMJC to join the Manhattan Project, America’s secret mission to build the atomic bomb.

The war intensified SMJC’s radio training, because it qualified students for coveted radio-operator jobs in the Army Signal Corps. In addition to engineering, a 1942 course in News Reading prepared broadcasters, as did three sections of Radio Speech. Speaking under cover from his Manhattan Project lab (students were told he was bombarding gold with neutrons at UC Berkeley’s cyclotron), Wiens urged women to take up radio, proclaiming in the campus San Matean that “Radio Work for Girls is Easier than Cooking.”

Laboe (known at SMJC as Arthur Egnoian) recalled that during the war a desperate general manager at San Francisco’s KSAN hired him on the spot. “I had a first-class radio-telephone and a radio-telegraph and a ham license,” Laboe told an interviewer. “His eyes got real big and he looked up at me and said, ‘You’re hired ... That license you’ve got, that first-class radio-telephone, I need that on my wall. All my engineers have been drafted and they’re in the service. I’m operating illegally and when I put that on my wall, I’ll be legal.’”

While the college worked toward FM capability, it arranged for students to air their work on now-long-departed local stations. These included KVSM, “The Voice of San Mateo,” and KSMO, owned by the Amphlett Printing Co., owners of the San Mateo Times. KSMO’s studios were on B Street near the railroad tracks and, according to the Bay Area Radio Hall of Fame, “listeners could tell if the SP Daylight was on time because it went past during a regularly scheduled newscast.”

Duplicating a pro broadcast experience

By 1950, thanks to fundraising by Wiens and college president Charles S. Morris, the college had built FM facilities at the Baldwin Avenue campus. Broadcast instructor Richard Marsh promised “a kind of activity that past radio classes have never experienced,” thanks to the 75-pound Magnecorder PT6 reel-to-reel tape recorder and Craftsmen AM-FM tuner installed in the audio racks. The new studio was large enough to hold the college’s chamber orchestra, because big commercial stations back then recorded live band music.

This insistence on duplicating a professional broadcast experience carried over into the College Heights years and made KCSM special. While many colleges had broadcast programs, few could put students live on an open-circuit station.

Recalled Rick Zanardi, an early 1960s graduate who later joined the KCSM staff: “Our program got people hired, because it was work. It wasn’t just going to school.”

In 1952, Charles S. Morris died suddenly after sustaining a heart attack at a Bulldog basketball game. FCC licensing paperwork was on his desk awaiting his signature. The call letters eventually assigned enshrined his initials as KCSM. With KCSM-FM going on air Feb. 11, 1953, radio at the college entered a new chapter.