Coyote Point

Million-dollar views and plentiful recreation uplifted CSM’s makeshift postwar campus

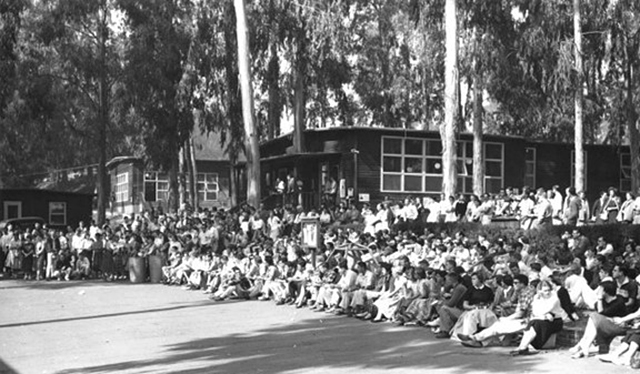

By 1947, returning World War II veterans seeking free schooling on the GI Bill strained San Mateo Junior College’s two campuses to bursting. Trustees leased the war-era Merchant Marine school on San Mateo’s scenic Coyote Point for a badly needed third campus.

Alumni fondly recall “The Point” as woodsy and welcoming, a veritable day camp for young adults. As well as million-dollar bay views and expansive sports fields (the Merchant Marine aimed to keep sailors busy on base), Coyote Point had a well-equipped cafeteria, two swimming pools and a large gymnasium—far better facilities than the college had ever known before.

Classes were held in the long, narrow barracks, some of them three desks deep and 20 desks wide. Plumbing and heating often failed. Airplane noise from nearby San Francisco International was even then a problem.

But to many SMJC students, Coyote Point was a paradise, purpose-built for fun.

“The cafeteria was the center of everything,” said Michael Koepf ’62. “We drank coffee and talked. We would meet people, hopefully girls.”

Koepf, a fisherman’s son from Half Moon Bay, said he had never before encountered such a broad range of people and ideas. Students from all over the Pacific Rim, including the future U.S. state of Hawaii, took advantage of peacetime to pour into the Bay Area. SMJC elected its first Asian American/Pacific Islander homecoming queen and student body president during this time, Moana Kaiwi ’52 and George Apaka ’52, as well as its first Asian American Women’s Athletic Association president, Mary Ellen Yee ’53.

“For a kid from Half Moon Bay meeting Korean kids and Pacific Islander kids, it was something. I realized there was a larger world out there,” recalled Koepf, who went on to become a novelist and screenwriter. His novel The Fisherman’s Son draws from his San Mateo County childhood.

Other students played bridge for hours on the cafeteria’s long redwood tables.

Student drama clubs posed against Coyote Point’s eucalyptus groves and Bayside rocks. Couples took romantic walks on the Bayside trails, including Betsy and Joe Atencio, who met at a campus dance and celebrated their 60th wedding anniversary in 2021.

“I loved the campus. I remember how lovely the campus was in those old wooden buildings. The wind blowing through the wonderful eucalyptus trees. You could go out on the bluff between classes and look out at the Bay,” Koepf said.

Fraternities—banned by college President Charles S. Morris but nonetheless popular—initiated pledges by sending them out onto the rocks to cope with the incoming tide. One student, 19-year-old Allan C. Musel, had to be rescued by a Coast Guard helicopter in a dramatic save that made nationwide news.

Academics were not neglected. Koepf recalled that his eyes were opened by Prof. Rudy Lapp’s “The Negro and the South in American History,” the first such class taught at a California community college. Lapp went on to write a Pulitzer-shortlisted history book on African-Americans in the Gold Rush. Both Koepf and George Boardman ’63 took journalism from Al Alexandre, who had just joined the faculty. Both became professional writers.

“That’s where I got my focus,” said Boardman, who worked for local newspapers and in PR for Ampex, long San Mateo County’s largest employer. “I discovered journalism. It set the course for what I’d do the rest of my life. I never really got out of it.”

Less uplifting, however, were administrative politics behind the scenes, especially after Morris’ death in 1952. College trustees agreed Coyote Point was a makeshift solution, but not on what to do about it. Some wanted the college to expand at its Delaware campus. Others, joined by Morris’ successor Elon Hildreth, wanted College of San Mateo, as it became known after 1954, to acquire Coyote Point permanently and to upgrade buildings there. Hildreth, in particular, alienated many locals with his desire to reserve the Merchant Marine commandant’s house as a CSM presidential residence.

Meanwhile, buses running hourly shuttled students among CSM’s three campuses. Students could take sequential classes at Delaware and Coyote Point or at Baldwin and Delaware—but not at Baldwin and Coyote Point, which were too far apart.

Eventually, the situation affected CSM’s accreditation status. In its 1954 evaluation, the committee cut its usual five-year accreditation to three until CSM could present plans for a single, unified campus.

Not long after, community leader Eleanore Druehl Nettle ’31 won election to the Board of Trustees on an explicitly anti-Hildreth platform. She led the search for new President Julio Bortolazzo and the creation of a community-led 25-year Master Plan. The latter gave rise to the College Heights campus and today’s three-college San Mateo Community College District.

Today, Coyote Point Recreation Area is managed by San Mateo County. The Commandant’s House, today a conference center, is the only building left from the Merchant Marine and CSM days. “The Point” is still a great place to have fun, with a marina, the Curiodyssey museum for children, spots to fish and wade, and walking trails like those that students enjoyed long ago.