How equity-based learning spread statewide

Students’ frustration at losing a valued program for learners of color spurred lawmakers in 1969 to create today’s EOPS

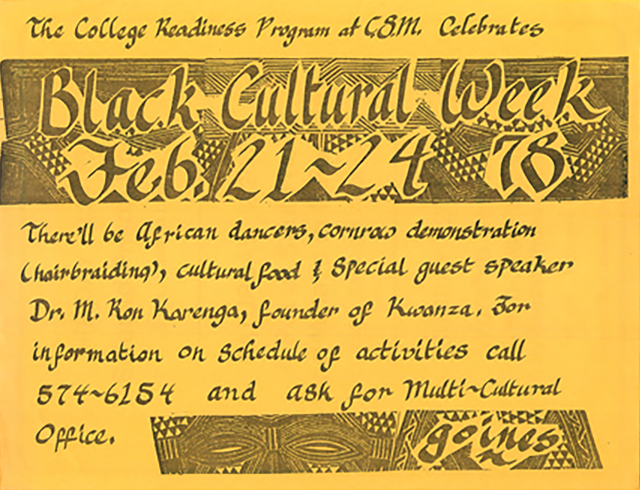

After CSM administrators backed away in 1968 from their landmark College Readiness Program amid a student uprising and massive police response, they found themselves criticized across the political spectrum.

Some influential people—both on the left and on the right—empathized with the CRP students and shared their frustration. They pointed out that hundreds of Black and Latinx students had enrolled at CSM expecting services that did not materialize, largely because College President Robert Ewigleben, who disliked the program, did not pursue available funds. Ewigleben sealed his fate, in these people’s estimation, by telling a state Assembly committee he would “over-react” to student protest if he had it to do again.

He was rebuked at the same hearing by the chancellor of the California Community Colleges, who urged preventive means “to preclude student-faculty confrontations by satisfying legitimate grievances.”

Months later, Democratic state Sen. Al Alquist, who represented San Mateo County, wrote the legislation that provided what he called Extended Opportunity Programs and Services for all community colleges in California.

“The Legislature has shown no hesitancy in passing laws aimed at curbing disorders,” Alquist said. “We will be terribly remiss if we fail to act to correct deficiencies in higher education which breed frustration and discontent.”

Alquist said his bill was inspired by a study commissioned by the state Board of Education of community college programs for disadvantaged students. The study looked at all such programs in the state. It described CSM’s College Readiness Program approvingly and in detail, calling CRP “unique among California junior colleges” and praising its work to confer “first-class academic citizenship.”

The study set forth no specific model, citing a lack of assessment data. It did make recommendations for the state as a whole and for colleges, including recruiting and hiring faculty of color, designing culturally inclusive curricula, questioning the validity of standardized testing, and making support for disadvantaged students a criterion for accreditation. Alquist’s bill provided for tutoring, counseling and other support toward such goals, and earmarked $3 million a year to make them happen.

To ensure his bill would pass a Republican state Senate and be signed by Republican Gov. Ronald Reagan, Alquist brought aboard as co-sponsor one of the most conservative members of the Legislature, Sen. John L. Harmer, R-Glendale, who had carried tough bills to control student unrest, including one to criminalize some protesters’ presence on campus.

Harmer’s views could be laughable. He tried, for example, to capture the nude musical Oh, Calcutta! on film so more people would be shocked. When it came to education, though, Harmer told reporters that failing to take positive action to help students of color was “playing right into the hands of the radical militants.” When the Senate Finance Committee stripped the funding from the bill, Harmer fought back, calling its opinion that funding minority students “was tantamount to giving in to demonstrations ... a blind and very narrow approach.” He marshaled his fellow Republicans to support the bill, and it became law in fall 1969.

Today, all of California’s 115 community colleges have Extended Opportunity Programs and Services (EOPS). At CSM, EOPS-funded programs were offered for years under the College Readiness Program name. They extended CRP’s philosophy and legacy into the 21st century. Today, up to 400 CSM students annually who face socioeconomic and/or academic challenges benefit from support first envisioned more than 50 years ago.