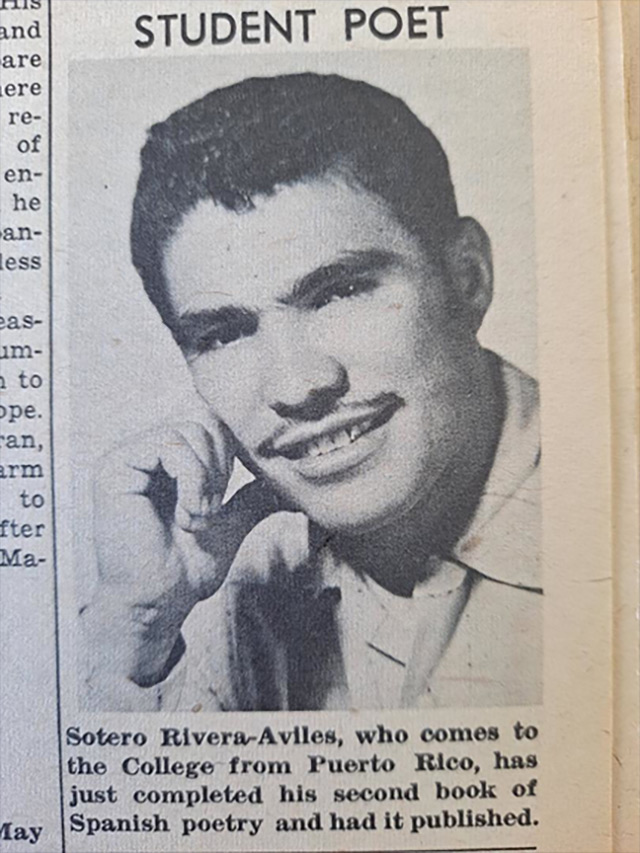

Sotero Rivera Avilés (CSM Class of 1959)

Poet of the Puerto Rican experience

Professor of literature

Disabled Korean War veteran

A serious war wound landed Sotero Rivera Avilés in a San Francisco hospital, and happenstance drew him to College of San Mateo. Rivera Avilés (1933-1994) found his literary calling while at CSM and went on to become one of Puerto Rico’s most honored poets.

Rivera Avilés was born in the small town of Añasco as the descendant of enslaved sugarcane workers. He enlisted in the Marines during the Korean War, where he lost an arm in action and sustained shrapnel damage to his left leg. Transferred to Letterman General Hospital for treatment, he appeared in a newspaper list of injured servicemen. A local family read the piece and took him in because he shared the same last name.

He liked to say that he got his poetry bug on the operating table. “He claimed he died and that the doctor heart-massaged him to revive him, and that’s when he got interested in poetry,” said his grandchild Raquel Salas Rivera, a literature PhD who received a 2021 National Endowment for the Arts fellowship to translate his work and is writing his biography.

Whatever the case, Rivera Avilés viewed his war injuries as transformative. He used them as tools to investigate the world and his place in it as a man, a Puerto Rican and a rural working-class person living at an intersection of colonial, racial, and economic trauma. By fall 1958, when he was a CSM freshman, he had already self-published his second book of Spanish-language poetry and was investigating the Beat poetry scene in San Francisco.

He was accepted at Stanford, but instead traveled through Mexico as a journalist before returning to his hometown. Rivera Avilés taught literature for decades as an adjunct professor at the University of Puerto Rico’s Mayagüez campus, not far from his home. In 1974, he won the Premio Ventana, an award given by the Puerto Rican journal of that name for meritorious literature in Spanish.

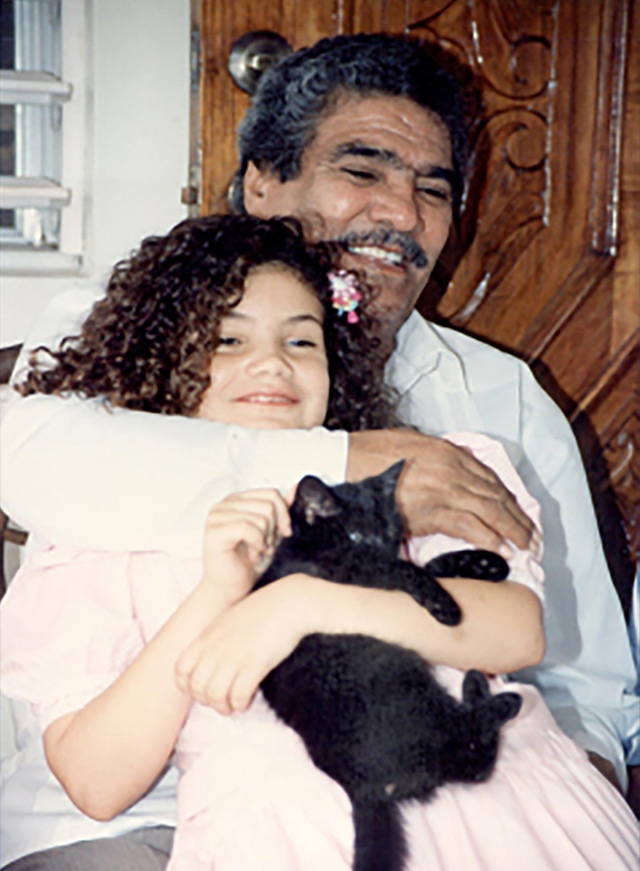

Though Rivera Avilés gets categorized with the 1950s poets called La Generación Guajana, he isn’t truly part of any group, Raquel Salas Rivera said. “Those 1950s poets tended to be a little metrocentric. My grandfather wrote about what it was like to be from a small town and having to migrate in order to have a livable life.

“He fell in love with poetry very deeply and maintained a commitment to the place where he was from and a commitment to tell the story of where he was from ... using words that have to do with agriculture, with cultivation, that are particular to his time and place and hard to translate.

“And he was a really good poet. He was a perfectionist.”

Domingo sin iglesia

Mi brazo artificial,

echado sin reparos sobre un mueble,

puede reír igual que un zapato sin rumbos,

destruido,

tirado a lluvia y noches

en el patio de entonces.

Comprendo su ironía

y he pensado

en viejos almanaques,

en toallas obscuras,

en vapores de incienso

cuando monjas

pasan bajo el calor de mi ventana.

... Y es que mi brazo artificial

comprende —

tiene ese don supremo de reírse

cuando piensa en el cura y las señoras viejas

que alzan su rabia y destrozan púlpitos

cuando ven pocos pecadores.

Churchless Sunday

My artificial arm,

carelessly tossed on some couch,

can laugh like an aimless shoe,

destroyed,

thrown to nights and rain

in what was once my yard.

I understand its irony

and have thought

of old almanacs,

of dark towels,

of whiffs of incense

when nuns

pass beneath my sweltry window.

.…You see my artificial arm

understands —

it has that supreme ability to laugh

when it thinks of the priest and the old women

that raise their rage and destroy pulpits

if they see too few sinners.

— Sotero Rivera Avilés

Translated from the Spanish by Raquel Salas Rivera

Read more of Sotero Rivera Avilés’ poems with Salas Rivera’s translations, courtesy of Action Books.