The Soccer Wars of 1931

Nine-year-old San Mateo Junior College made a bold statement of identity in bucking convention to vote soccer a major sport

For more than a century, America’s most popular college sport has been football. In 1931, it figured into then-San Mateo Junior College’s first big controversy – whether to depart from tradition by declaring soccer equal to football as a major sport.

The question facing student leaders: Should SMJC soccer players receive varsity Block S letters like players of football, basketball and other sports in the Northern California Junior College Conference, or merely the small Circle S given to golfers, rowers and others who competed on essentially a club level?

In the end, students sided with the soccer players – but not before hashing out questions over identity, convention and whether 9-year-old SMJC would be less of a “real” college by following its own star.

From the start, football was big at SMJC. Coach Murius McFadden, hired a year after the 1922 founding, led the Bulldogs to eight league titles in 20 years and the state championship in 1928.

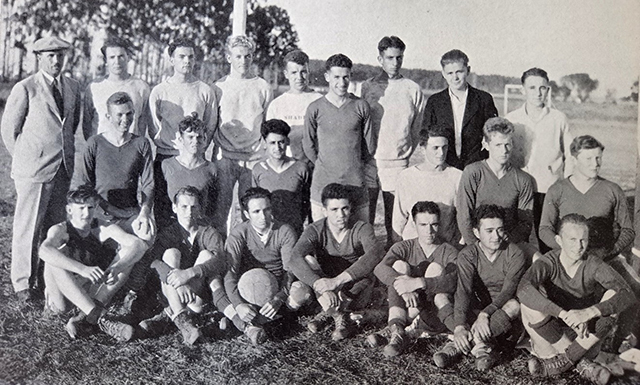

Unlike at many colleges, however, Bulldog soccer was not far behind. SMJC formed its first team in 1926 as founding members of a soccer league that included UC Berkeley, Stanford, San Jose State and the University of San Francisco. From 1926 to 1931, the Bulldogs had won their conference title five of six years. Moreover, the schools they crushed were all four-year programs: San Mateo was the only community college in its league.

Contributing to its success was SMJC’s relatively large number of students who were born or studied overseas, where soccer is far more popular. One 1930s president of the Board of Trustees, A.S.W. Grundy, had played soccer in England, and his son Stephen was on the Bulldog team. Other early players came from Peru, Norway and Turkey, among other countries.

The players’ request threw student leaders into a frenzy. The U.S. voting age was 21 then, and campus government absorbed much of the energy that might otherwise have gone to general elections and public affairs. SMJC’s Executive Council decided that the student body constitution had to be amended by vote to permit the soccer letters.

The campus San Matean newspaper favored soccer, and enraged football partisans by reporting soccer and football wins in equally gigantic headlines. “The kickers’ performance merits equal recognition,” editor Charles Alexander wrote. Accusing the San Matean of “outside influence” in an athletics issue, the Block S Society cited “tradition” in opposing the Block S for soccermen. So did The Forum, the school debate club.

A campus assembly to debate the issue became so rowdy that Dean of Men Harold Taggart broke it up and sent everyone home.

On Nov. 3, 1931, students voted 228-87 to amend the constitution to allow soccer letters. But the question was not settled, since the constitution required 400 votes cast for an amendment to pass.

Taggart said he didn’t think the campus would survive a second vote. So SMJC’s Board of Control, which regulated Bulldog athletics, agreed to award Block S letters to male competitors in every sport. Women athletes, governed in those pre-Title IX days by a separate organization, gained the right to wear Block S’s on their jerseys.

And so it went until 1941, when America’s entry into World War II shut down most sports. Soccer persisted because the few men on campus played British Royal Navy teams stationed on Treasure Island.

After the war, CSM ceased to play varsity soccer. However, the college’s internationalism and diverse student body continue to shape its identity today.