Robin Heyeck

Fine-art letterpress printer and paper marbler

CSM professor of English, 1965-2001

Instructor in CSM’s feminist Re-Entry Center for women

“I saw the invitation I had typeset coming off the press and I thought, I’m going to do this for the rest of my life.”

Nearly 50 years ago, Robin Heyeck created the first Women in Literature class at College of San Mateo. As an instructor in CSM’s Re-Entry Center in the 1970s, Heyeck helped dozens of women raise their educational horizons.

Heyeck’s adventurous spirit and her love of learning and of poetry drew her to the work she is best known for today. As owner of The Heyeck Press in Woodside, Heyeck prints fine limited editions of poetry and prose, with metal type on a Chandler-Price platen press. She taught herself to marble paper and often uses marbled papers to illustrate her books. Several of them are bound in marbled silk.

Her books are collected by museums and libraries around the world. The Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York City plans a January 2023 exhibition of late 20th century marbling that will include her work.

As Heyeck tells it, owning a press was her husband John’s idea.

“In 1973, my husband said, ‘You know what I’ve always wanted?’ I kind of held my breath. ... ‘A printing press.’ I asked, What for? ‘I don’t know. To print things.’”

Of the pair, it was Robin Heyeck who fell lastingly in love with the art: “I saw the invitation I had typeset coming off the press and I thought, I’m going to do this for the rest of my life.”

She entered the field when letterpress printing had given way to faster but less elegant electronic typesetting and offset printing. She bought the large, handsome press she uses today at a Stanford surplus-property auction in 1981 for $350.

Heyeck’s first products included CSM’s annual student Poetry Fair anthologies and a collection of feminist cartoons by student Judith Hanson, Re-Enter Laughing. Soon, poets were submitting their work to her for books. The Heyeck Press pays all production and publication costs and pays its authors standard royalties.

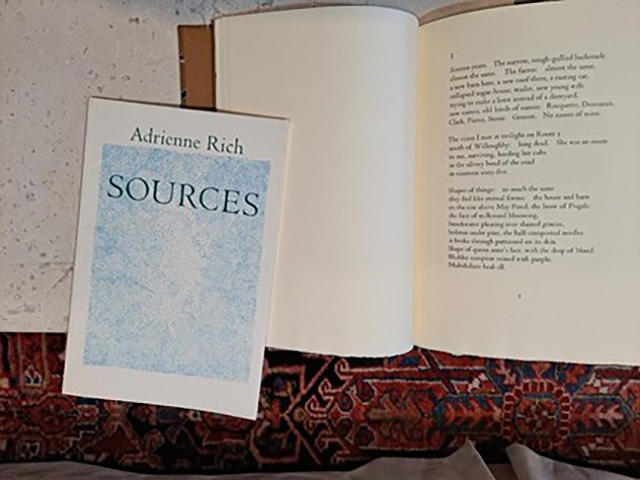

In 1983, Heyeck approached Adrienne Rich, the pathbreaking feminist poet, to print one of her books. It was a big leap because Rich was at the top of her field—both in technical skill and in audience reach.

Rich interviewed Heyeck thoroughly and liked her feminist credentials and the quality of her printing. They agreed that Heyeck would print and publish a fine first edition of 300 copies of Rich’s manuscript Sources. A few months later Rich telephoned and asked, “Couldn’t you just do a small paperback edition of 5,000?”

“This was the year of the big storms,” Heyeck remembers. “I was dealing with a landslide. Our driveway went out for 18 months. I said, I can do a thousand.

“So I was bringing boxes of paper down the deer path on the other side of the property. I was taking the printed sheets up the deer path to the bindery in San Francisco. Then I was carrying boxes of the bound books down the hill and wrapped packages of books back up to mail.

“The 1,000 sold out within a couple of months. I printed 2,000 more, then 1,000.”

Sources then was included in Rich’s The Fact of a Doorframe: Poems Selected and New 1950-1984 from her regular publisher, W.W. Norton & Co.

An added dimension to Heyeck’s work is that she does her own marbling. In this craft, pigments are made to float in a pan of water and carrageenan, combed into the pattern Heyeck has designed for the specific edition, then captured on an overlaid sheet of paper with meticulous care. Each sheet is unique, a moment of motion fixed in time.

Heyeck says she made many mistakes while learning to marble. She narrates this journey in a two-volume artist memoir, Marbling at The Heyeck Press, in which samples of her marbling, including a range of common errors, parallel her story of learning her craft. In this way, Marbling at The Heyeck Press continues her work as an educator.

Though Heyeck ascribes her success to liking the “fine, picky work” of printing, she also stresses the broader value of self-confidence. It’s a value she has tried to foster since her earliest days at CSM.

“In consciousness-raising groups we’d go around the room and I’d suggest, ‘Tell us three things you’re good at.’ This was hard for women back then. A woman wasn’t supposed to blow her own horn. Some of them just couldn’t! Occasionally I’d say, ‘I like my brain because it amuses me.’

“Women need self-confidence. We needed it back then and we need it still.”