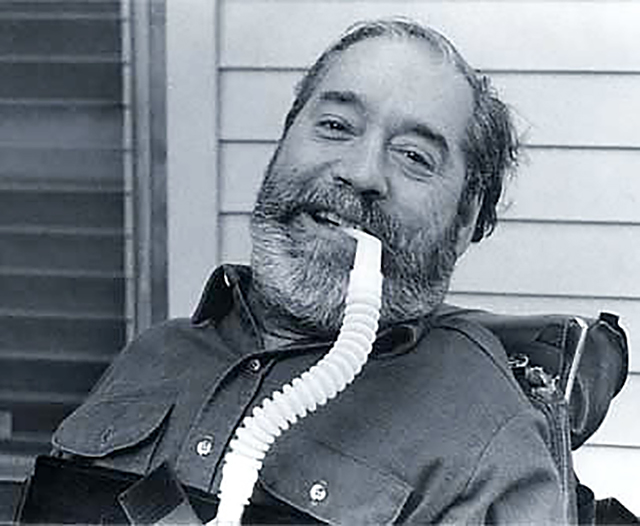

Ed Roberts (CSM Class of 1962)

Disability rights pioneer

First quadriplegic to graduate from CSM and UC Berkeley

Founder of America’s first disabled-students program

First severely disabled chief of the California Department of Rehabilitation

First severely disabled MacArthur “genius grant” recipient

“For people to stare at me did not hurt me. I realized I could enjoy it. ... I could enjoy being stared at if I thought of myself as a star and not just a helpless cripple.”

College of San Mateo graduate Edward V. Roberts (1939-1995) did more than almost anyone to end this shadow existence for disabled people, both by example and by his public service. Rendered quadriplegic by polio at the age of 14, Roberts attended CSM and then UC Berkeley while breathing with a respirator strapped to his wheelchair.

He taught political science at Berkeley; organized fellow disabled students into what became the Center for Independent Living and the Ed Roberts Campus; was named by Gov. Jerry Brown to lead the state Department of Rehabilitation; and used his 1984 MacArthur Foundation “genius grant” to co-found a think tank for disability rights.

Among Roberts’ historic firsts, he recalled fondly his time at CSM, where administrators and staff went to great lengths for him to succeed.

As a high school student in Burlingame, Roberts attended class from home via telephone. His mother, Zona, thought he needed academic challenge and a social life. She demanded that he get classroom instruction, an extraordinary ask in the 1950s for a seriously disabled student. Roberts at first felt scared and shy at this public exposure, then realized “It was like being a star.”

The Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) mandating accessible walkways was decades in the future. At CSM, burly student-athletes vied to haul Roberts, his chair and his respirator out of an attendant’s car and up and down the stairs. Visionary counselor Jean Wirth, later coordinator of CSM’s College Readiness Program, urged Roberts to aim high. He graduated from CSM in 1962.

“I was interested in political science,” he told the California State Archives’ Regional Oral History Project in 1994. “[Jean Wirth] said, ‘Well, if you’re going to be into politics, the only place to go is Berkeley. Let’s go over.’”

Berkeley had never graduated a quadriplegic student. Neither Roberts nor his glowing CSM recommenders mentioned Roberts’ disability in his application. When time came for him to enroll at Cal, Wirth and CSM Dean of Students Philip Morse personally escorted him to campus. They met with Morse’s equivalent at Cal, Arleigh Williams.

“We all kind of agreed that this would be the place for me,” Roberts remembered. “But it wasn’t going to be easy. It all seemed sort of like a rough dream.”

Roberts slept in an iron lung, as he did the rest of his life. It weighed 800 pounds, too heavy for dorm floors. Cal decided the only place to safely house Roberts was in Cowell Health Center, the university infirmary near the top of the hilly campus.

Morse and Wirth helped Roberts wrest college funding from the state Department of Rehabilitation, which initially rejected his claim on the grounds that a quadriplegic educated in political science would never find a job.

Soon, another quadriplegic joined Roberts at Cowell, then others. They rolled down the hill in formation to their classes and called themselves the Rolling Quads. They founded America’s first Physically Disabled Students Program, precursor to the Center for Independent Living (CIL). Their positive, proud expression of disability identity became the center’s core value, as revolutionary as the actual services provided.

To establish the center, Roberts had to travel to Washington, D.C. Airlines wouldn’t let him take his respirator on board. So Roberts flew coast-to-coast while “frog-breathing” – a Herculean exertion – forcing air into his lungs by using muscles in his face and neck.

Roberts earned his BA in political science in 1964 and his MA in 1966. He taught for seven years at Berkeley, then at East Palo Alto’s Nairobi College, a Black-focused alternative school led by former CSM College Readiness Program director Bob Hoover. Ultimately, Roberts tilted toward public service and not academia.

Roberts married and had a son. From 1972 to 1975, he headed the Center for Independent Living, then led the state Department of Rehabilitation until 1983. As director, he sought to change the department’s “thinking they know more about what you want and need than you do, which I think is dumb. Nobody knows more.”

In 1977, Roberts took part in an occupation of the U.S. Department of Health, Education and Welfare offices in San Francisco to demand implementation of a four-year-old law banning disability-based discrimination at federally funded entities. The 28-day action, known as the “Section 504 Sit-In,” led to the creation of the operational principles that now underlie ADA compliance. It, like all Roberts’ work, convinced more people that disability was a societal issue to be handled politically, not an illness, and not a shameful problem to be borne by an individual alone.

In 1983, Roberts left state service and co-founded the World Institute on Disability, an Oakland think tank that fought for the ADA’s passage in 1990.

When he died of heart failure five years later, a memorial service was held in the Dirksen Senate Office Building in Washington, D.C. In 2010, the state of California designated each January 23 as Ed Roberts Day to prompt disability awareness in schools.

Roberts’ custom-built motorized wheelchair is in the Smithsonian Institution’s National Museum of American History, where it illustrates his resourcefulness, joie de vivre and drive. The chair has a light for night driving; slots for his respirator and a portable ramp; a reclining power seat; and a sticker on one side that spells out in purple letters, “YES.”

Read Roberts’ interview for the California State Archives’ Regional Oral History Project.

Learn more about the Ed Roberts Campus in Berkeley, which houses CIL and other agencies run by and for disabled people.