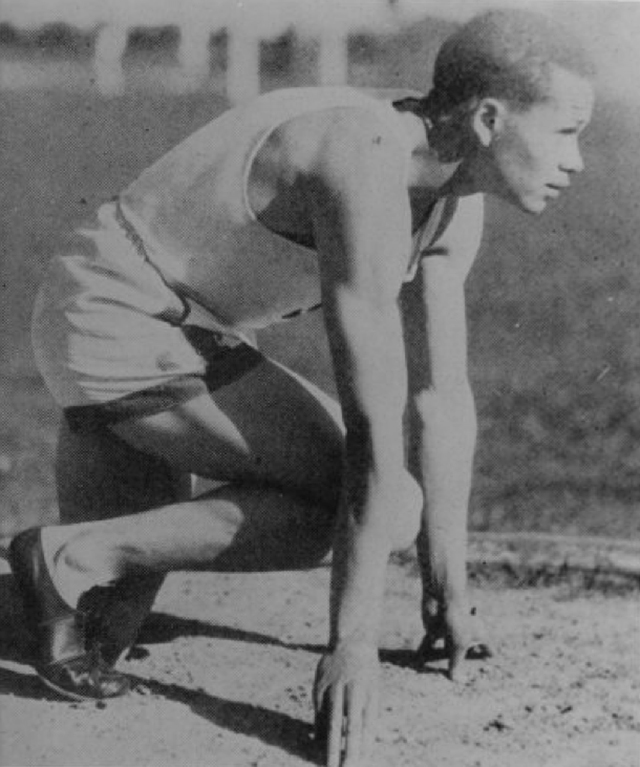

Archie Williams (CSM Class of 1935)

1936 Olympic champion, 400 meter run

Pilot, flight instructor and trainer of Tuskegee Airmen

Meteorologist with the Army Air Weather Service, retiring as lieutenant colonel

Math and computer science teacher for 22 years

“Every race that you run is a final. If you don't win, then it is final.”

Archie Williams and his cousin, Les Williams ‘39, endured systemic racism to achieve high-profile milestones in science, aviation and athletics.

Archie Franklin Williams ’35 (1915-1993) grew up in Oakland. His parents rented their third-floor rooms to UC Berkeley students, including one who “would give us younger kids a whack on the rear if we got to be a nuisance” during studying. Archie got indifferent grades at in high school but dreamed of flight and excelled at building model airplanes, once winning an award from the OaklandTribune.

In 1934, the East Bay did not yet have a junior college. So Williams enrolled at CSM (then San Mateo Junior College) with the goal of transferring into Cal’s engineering program.

At CSM, Williams laid the math and science groundwork that would help him to become one of the first African-American flight instructors, one of the first Black meteorologists, and a STEM teacher. As an educator, he was so beloved that a movement was launched in 2017 to rename his former workplace, Novato’s Sir Francis Drake High School, after him.

He also ran track for the Bulldogs, launching a career capped by a gold medal in the 400 meters at the 1936 Olympics in Berlin. His performance, along with that of Jesse Owens and 16 other African-American athletes, mocked Adolf Hitler’s doctrine of Aryan supremacy and opened new vistas of opportunity in sports.

In San Mateo, the 19-year-old Williams boarded with a local family for five dollars a week, exactly the sum he made as a part-time golf caddy.

In a 1992 oral history for UC’s Bancroft Library, Williams, colorful but unassuming, described CSM coach Oliver “Tex” Byrd’s team.

“In high school, you don't have much competition. ... you're not pushing it to the limit. You get in junior college, you're sort of halfway between high school and college. Every now and then you run up against a real good runner, a good athlete.

“In junior college, we would compete against the Cal freshmen and Stanford freshmen. You had an idea how to rate yourself. How well you would do against those guys would tell you how you would do later on.”

As a Bulldog, Williams won 19 of his 20 races.

“In those days, you worked out every afternoon from 3:00 until 5:00,” he said. “In fact, in San Mateo, we didn't have a track. The baseball team would go down to City Park [today’s Central Park] to play baseball. We had to ride the bus up to Burlingame High School to run and practice track, which is five miles away.

“When we got back from there, we never got a hot shower. All the baseball players used up all the hot water. We were a bunch of kids; we didn't care.”

As well as a baptism in competitive athletics, CSM gave Williams his first taste of trigonometry and calculus. He was surprised to get A’s, still more so that Coach Byrd noticed them. Like Williams’ next coach, Berkeley’s legendary Brutus Hamilton, Byrd trained “the whole person,” Williams said.

“It's tough to take those courses, the courses I took in junior college. If I took those at Cal, I would be competing against a bunch of hotshot high school seniors and I would have been out of my league. But I think everybody I was with in junior college was in my same category.”

Byrd followed his athletes’ grades in part because he sent nearly all of them to four-year programs, notably Stanford and USC. Williams, though, went to Cal in spring 1935 as a sophomore bent on academics. In those days, he observed, schools often recruited, then redshirted, Black athletes, merely wanting to foreclose on their playing for opposing teams.

“I didn’t care. I was going to play in the physics lab,” Williams said.

Within a year, however, he morphed into a world-class athlete, shaving more than 2 seconds off his 400-meter time. He broke the world record in the 400 at the 1936 NCAA Championships with 46.1 in a preliminary heat, then won the final with 47.0. He also ran his 200-meter personal best there, 21.4 seconds.

The NCAA result qualified Williams for the 1936 U.S. Olympic Trials, where he won the 400 in 46.8. He headed to the Berlin Olympics on a ship that offered no place to train, then bunked in the Olympic Village’s segregated U.S. quarters while trying to make up for lost training time.

In the 400, Williams came from behind to win the gold medal.

“I was happy,” he said. “It was like a dream. You were dreaming you were in something that you thought about before. ‘What am I doing here? Is this me?’ In fact, when it was over and I came back, did that really happen? Did I really do that?”

Owens, with his four gold medals, has overshadowed Williams in the history books, but, as Williams observed, “Hitler wouldn’t shake my hand either.”

Soon after, a torn hamstring ended Williams’ track career. He earned his mechanical-engineering degree from Cal in 1939. By then, he was already en route to his next achievement. In Berkeley’s student Civilian Pilot Training Program, he was learning to fly.

“This was sort of a prewar-type thing,” Williams said. “They were trying to get a corps of private pilots.”

After training at Oakland Airport, Williams maintained planes in exchange for flight hours. He earned his instructor rating, taking students informally because firms didn’t hire Black pilots to teach.

In 1943, Williams joined the flight school at Tuskegee Institute (now University), Ala., that trained the Army Air Corps combat pilots known as the Tuskegee Airmen. As America’s first Black combat pilots, the high-profile Airmen represented strength and hope to millions who endured Jim Crow segregation while nonetheless aiding the U.S. fight to end fascism abroad. Williams and other Black civilian instructors gave the Airmen their initial flight training.

“They were harsh on us, but they were determined that we were going to do things right. We couldn’t give them that buddy-buddy stuff,” recalled a younger cousin, Les Williams ’39, who earned his wings in Tuskegee’s 13th class.

Archie Williams was too old, at 27, to be an aviation cadet. Yet his skill set of both a pilot’s license and a STEM degree was rare and valuable to the Army. Williams was sent to UCLA for master’s-level training in meteorology, then commissioned a second lieutenant. His cohort of 14 became the first Black meteorologists in the United States. Williams drew weather maps, made forecasts, and taught Intro to Flying for the all-Black 99th Pursuit Squadron back at Tuskegee. After President Truman signed the order desegregating the military in 1948, Williams served in the Air Weather Service (now the Air Force Weather Agency). He served in the military for 21 years.

“Truman was our main man,” Williams said. “He was the one who integrated the military. The main thing, they found out that [segregation] doesn't make sense. They were losing money. You've got some people who can do something; they've got a skill that you need.

“Since (I) had training (in both flight) and weather, (I) would jump in that plane and check the weather. I used to go up and fly around and see how the weather was, call back and say, ‘It’s OK to fly.’”

Williams remained in the Air Weather Service for the rest of his military career. During the Korean War, he logged four B-29 combat missions over North Korea. As a forecaster with the 20th Operational Weather Squadron at Yokota Air Base, Japan, he prepared forecasts and briefings for all branches of the U.S. armed services at 115 installations in the Pacific theater. He retired in 1964 at March Air Force Base near Riverside as a lieutenant colonel and command pilot. Before retiring, he completed his coursework for his teaching credential. He went to Marin County because a former Cal training buddy was a superintendent there. He also coached track.

It was “beautiful,” Williams said of teaching. “It was easy. I loved it.”

Archie Williams died in 1993. In 2017, his former students and others in Marin launched a drive to more prominently honor Williams’ contributions.

Former student Ned Farnkopf told KPIX-TV: “You know the Scouting slogan, ‘Do a good turn every day’? Archie did multiple good turns every day. That’s the way he wanted to go through life.”